Inaccurate—and sometimes preposterous—news stories have been circulating since mankind first began stringing words together in a sentence. History shows that even reputable publications sometimes pick up questionable stories and run with them.

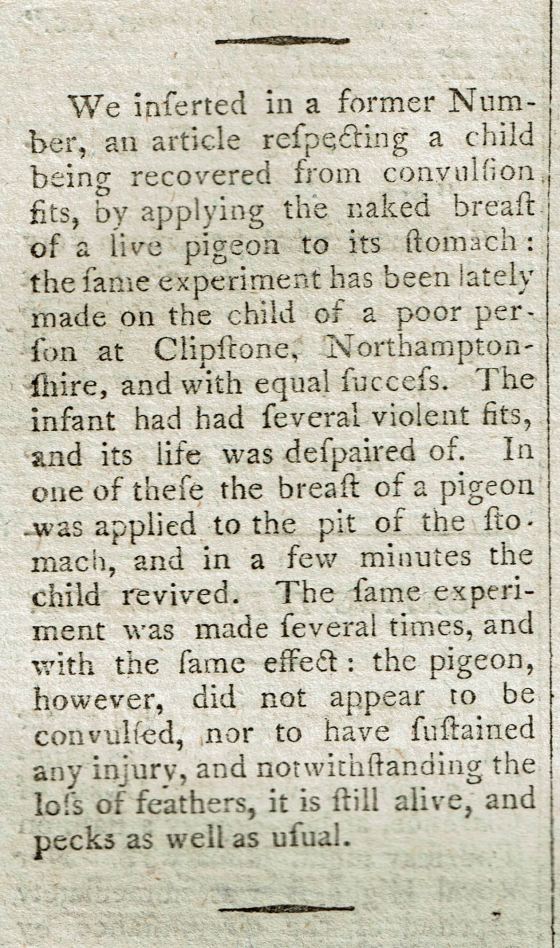

To illustrate the point, here’s a news item I found in a 1798 issue of Sporting Magazine about a revolutionary medical treatment:

To illustrate the point, here’s a news item I found in a 1798 issue of Sporting Magazine about a revolutionary medical treatment:

We inserted in a former Number, an article respecting a child being recovered from convulsion fits, by applying the naked breast of a live pigeon to its stomach: the same experiment has been lately made on the child of a poor person at Clipstone, Northamptonshire, and with equal success. The infant had had several violent fits, and its life was despaired of. In one of these the breast of a pigeon was applied to the pit of the stomach, and in a few minutes the child revived. The same experiment was made several times, and with the same effect: the pigeon, however, did not appear to be convulsed, nor to have sustained any injury, and notwithstanding the loss of feathers, it is still alive, and pecks as well as usual.

This may read like nothing more than a bit of Regency-era quackery, but at least the story had a happy ending: both patient and pigeon survived.

The pigeon was not so lucky in the following account of a similar encounter, which I found in The Monthly Gazette of Health, Vol. IV for the Year 1819 by Richard Reece, M.D. of London:

Epilepsy.—An intelligent gentleman of Gloucester, informs us, that the parents of a young man residing at Fairford, who had been for four or five years subject to epileptic fits, applied (by the advice of a friend) a live pigeon to the pit of his stomach during an attack of the paroxysm. The fit terminated much sooner than usual, and the pigeon on being removed was observed to be stupid. On a return of the fit the same pigeon was re-applied to the pit of the stomach, and soon afterwards the patient recovered, and the pigeon exhibited some symptoms of being convulsed.

These two stories aren’t necessarily representative of the state of early nineteenth century medicine, but they do make an important point: In Regency-era England, physician-prescribed medical treatments (like blood-letting, laxative-induced purging, and applying leeches) often did more harm than good. It was natural, then, for people to search for alternatives, like folk remedies, to cure what ailed them.

After all, pigeons were plentiful; and with stories like these fueling people’s imaginations, desperate families (and a few untrained members in the medical profession) had nothing to lose by turning to pigeons to ease the symptoms of a loved one’s illness.

Medical anthropologist and author Kyra Kramer recently did a guest post about Regency medicine on Maria Grace’s blog, Random Bits of Fascination. It’s an interesting read with nary a mention of pigeons. I hope you check it out.